Resource Center

All ContentBlogCase Studies

- athenahealth

- March 11, 2025

- 9 min read

10 ways patient engagement tools enhance healthcare

From scheduling to billing and care coordination, these patient engagement tools help patients and practices thrive. Read moreYou may also like

- Christine Davis

- April 02, 2025

- 5 min read

athenahealth products

An EHR built for behavioral health

Behavioral health providers need technology that supports their unique needs. See how we deliver.

Read more

- athenahealth

- April 02, 2025

- 7 min read

Electronic health record

The hidden costs of an unreliable EHR

When your EHR doesn’t live up to its promise, it can end up costing you more. Explore what to look for in a reliable system.

Read more

- Christine Davis

- April 02, 2025

- 8 min read

athenahealth products

athenaOne® features that reduce patient charting time

See how EHR tools, accelerators, and Ambient Notes are helping clinicians document faster.

Read more

- athenahealth

- April 02, 2025

- 8 min read

Shared savings VBC

Guide to Medicare accountable care organization models

Do you understand CMS' ACO payment models? Read our guide to find programs for your practice.

Read more

- Christine Davis

- April 02, 2025

- 5 min read

athenahealth products

An EHR built for behavioral health

Behavioral health providers need technology that supports their unique needs. See how we deliver.

Read more

- athenahealth

- April 02, 2025

- 7 min read

Electronic health record

The hidden costs of an unreliable EHR

When your EHR doesn’t live up to its promise, it can end up costing you more. Explore what to look for in a reliable system.

Read more

- Christine Davis

- April 02, 2025

- 8 min read

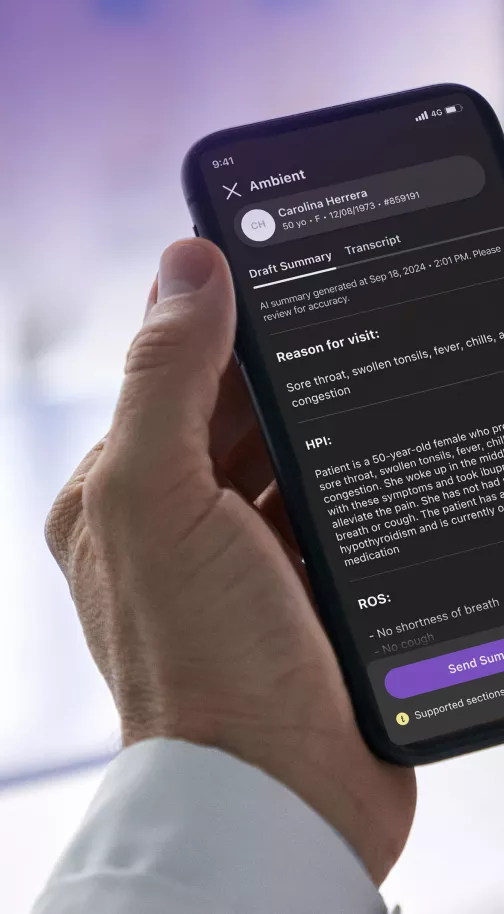

athenahealth products

athenaOne® features that reduce patient charting time

See how EHR tools, accelerators, and Ambient Notes are helping clinicians document faster.

Read more

- athenahealth

- April 02, 2025

- 8 min read

Shared savings VBC

Guide to Medicare accountable care organization models

Do you understand CMS' ACO payment models? Read our guide to find programs for your practice.

Read more

- Christine Davis

- April 02, 2025

- 5 min read

athenahealth products

An EHR built for behavioral health

Behavioral health providers need technology that supports their unique needs. See how we deliver.

Read more Empower your practice

AI powered patient engagement

Learn how AI tools can help improve patient loyalty and outcomes.