A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, both providers and patients have become more comfortable with telehealth and are pleasantly surprised by the quality and range of care possible. In fact, athenahealth data show that 32 times as many virtual visits are happening now than before March 2020.

Telehealth provides a convenient way for patients to see providers, especially after work or on the weekends. But what is the effect on physicians? Are they as happy as patients to be able to conduct visits from their living room on a Saturday morning? It turns out, by and large, they are.

Beginning in 2020, athenahealth has been conducting research into the use and impact of telehealth. The research includes analysis of de-identified data from across athenahealth’s network of customers as well as conversations with providers. This article is based on that research.

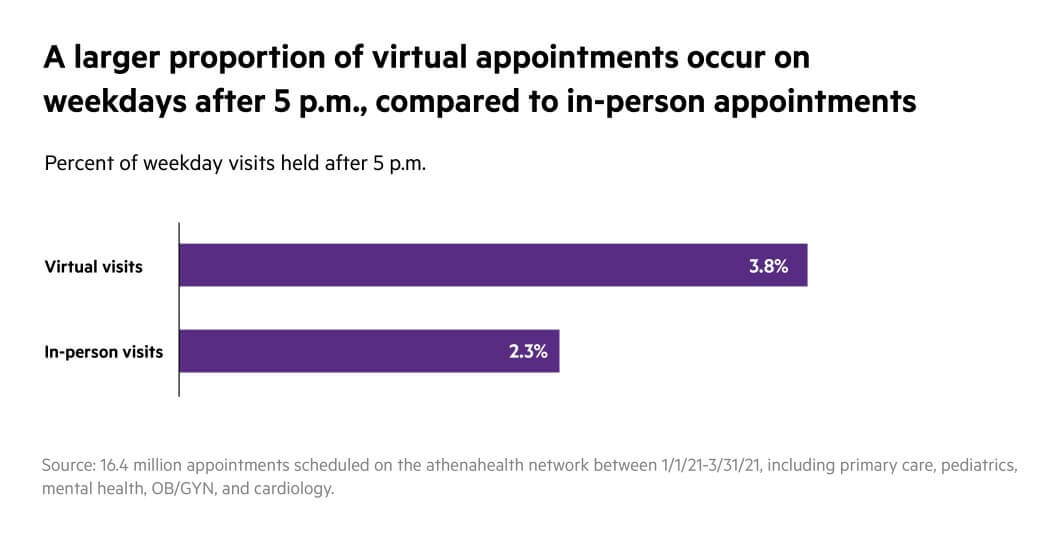

Virtual visits are more likely to take place after hours

Before the pandemic, almost all appointments occurred in the clinic, whether they were during business hours or not. Now, a higher percentage of virtual appointments occur after 5 p.m. as compared to in-person visits, suggesting that virtual care offers an easier, more convenient option, particularly after a long workday.

Recent discussions with physicians using athenahealth products suggest that patients aren’t the only ones who value this convenience. Many providers like that they don’t have to commute to the office on weekends, letting them spend more time with family. Others were glad to be able to leave earlier on weekdays, instead slotting in one or two short telehealth appointments based on their evening plans — in fact, Jeff Drasnin, M.D. of ESD Pediatric Group in Milford, Ohio shared, “I am home for dinner every night.”

Most physicians have not changed the appointment times they offer

Physicians have shared that, for the most part, they are not adding new weekend or evening appointment slots now that they are relying largely on telehealth. Rather, they are converting off-hours appointments that would otherwise have been in-person to virtual visits.

One behavioral health practice in California noted that some providers “add an hour or half an hour before or after their schedule [with virtual care]” because they are not commuting, but by and large physicians are keeping the same core hours as before the pandemic.

Other providers shared that they are actually being more strict about maintaining boundaries and not adding after-hours or evening appointments. Largely, this is a conscious choice designed to maintain their work-life balance as so much else about their practice is in turmoil.

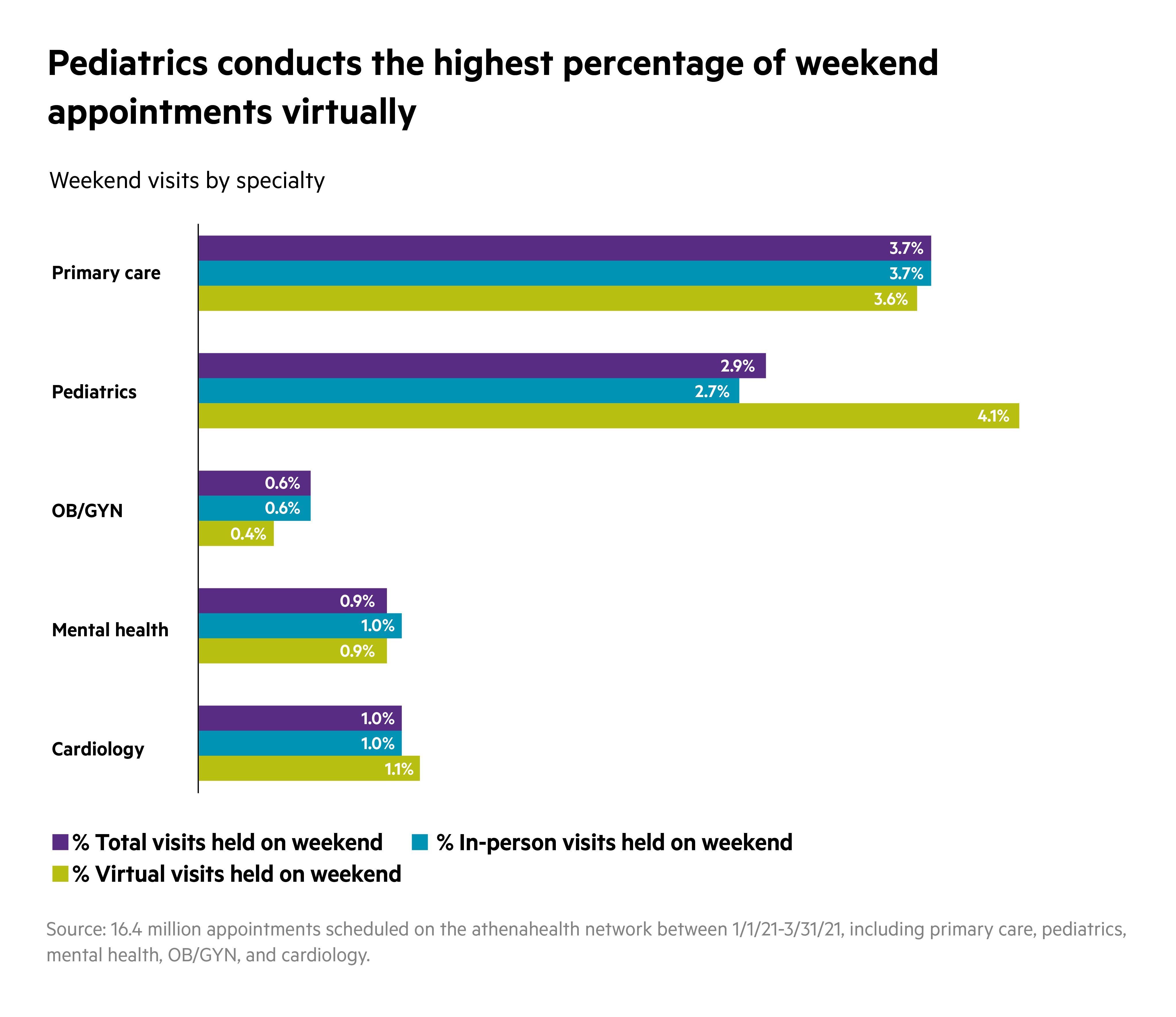

Pediatrics is taking particular advantage of telehealth during off-hours

Some specialties have always offered more weekend and evening appointments than others, like primary care and pediatrics. Now that telehealth is a viable option, pediatricians seem to be taking significant advantage of off-hours and weekend virtual appointments.

While most specialties included in this study scheduled more visits virtually after 5 p.m., pediatrics was the only specialty to also schedule more of their weekend visits virtually, making this part of the job less disruptive to their personal lives.

Virtual care can enhance work-life balance — as long as physicians have a say

Most providers indicate that, overall, telehealth has given them more flexibility and predictability to take part in home and family life. The key was to let the physicians decide when to offer virtual visits and how to fit them into their patient schedule.

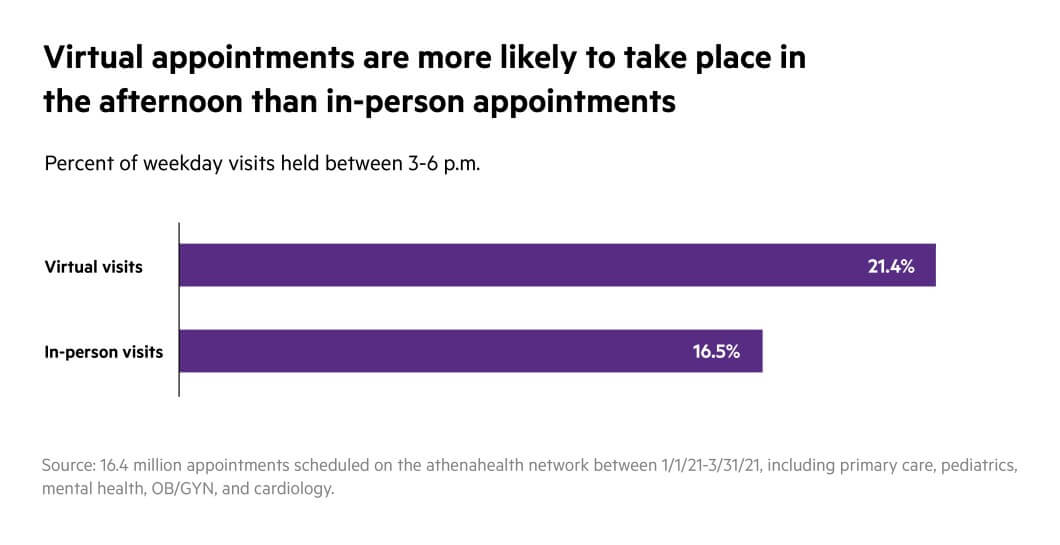

One good example of this is that physicians are scheduling more telehealth visits in the afternoon, allowing them to avoid evening rush hour or even make it to their children’s after-school events.

“My son's games are at 4:30,” says Drasnin. “I try to schedule my telehealth days for when he has his games. I do my telehealth from the parking lot. At 4:30 I close my laptop, get out of the car, and go into the game. If I’d scheduled patients at the office until 4:30, I couldn’t have made it.”

Most practices indicate they will continue to allow physicians to use telehealth in whatever way works best for them and their patients. Many anticipate a future where physicians will set specific days of the week that are telehealth-only scheduled around their personal commitments, and that off-hours appointments will continue to be done virtually whenever possible.

“Maybe I have a parent who wants to work noon to nine p.m.,” says Kemi Alli, CEO of Henry J. Austin Health Center in Trenton, New Jersey, “or maybe want to work from eight to 12, take a break from 12 to four, then come back on four to eight. One of the things I want to start thinking about is how can we really create flexible systems…given that [telehealth] is going to be around for a while.”

When deployed correctly, virtual care can provide greater convenience and access for patients, while also offering providers welcome flexibility to work from home, to see their families, to make weekend plans — even to travel.

As Drasnin says,

“Don’t let your work get in the way of your life.”