Article

The new ground rules of patient engagement

By Lia Novotny | July 27, 2017

Physicians are no longer the only decision-makers in healthcare.

As patients pay more of their own costs — and gather more of their own information — doctors and patients are increasingly working together to evaluate treatment options and make care plans.

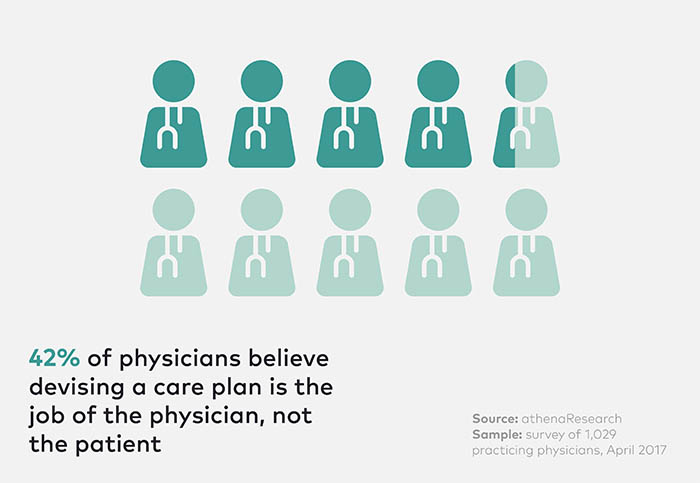

In a recent athenahealth survey of more than 1,000 doctors, well over half of respondents said they believe decisions concerning preventive care, wellness, medication management, and care planning are responsibilities a physician and patient should share.

But the dynamics of shared decision-making can be a challenge for both sides. athenaInsight spoke with two chief medical officers about this new approach to patient engagement — and how it looks in practice.

athenaInsight: One of the most difficult challenges many patients face is navigating the intricacies of the healthcare system. Some patients still want doctors to tell them what to do, but 65 percent of our respondents consider handling the many handoffs in healthcare — from labs to physical therapy to medication — to be a shared responsibility. What does it look like when patients are involved in managing their own care?

Tad Jacobs, D.O., chief medical officer, Avera Medical Group, Sioux Falls, S.D.: First and foremost, this means the patient should ask questions. Care teams want you to be engaged and to have questions for us. That could be about how to treat an illness or injury, alternatives to the recommended treatment, and — yes — questions about costs. The days when a doctor would bristle because of patient questions are, happily, long gone.

Adam Myers, M.D., chief medical officer, Texas Health Physicians Group, Arlington, Texas: I agree, and I would add: Don't be afraid to be vulnerable with your physician. Too often, the patient, out of respect or embarrassment, refrains from asking clarifying questions that can actually change their outcome, or isn't honest about their behaviors. Being candid and open about what you're actually doing is critical.

athenaInsight: Our survey data show that 42 percent of physicians still believe that devising a care plan is the job of the physician, not the patient. How do you train doctors and patients to open up that process?

Myers: The physician has to make it safe for patients to speak. Research suggests the average physician interrupts the patient about 17 seconds into their response to “What brings you here today?" — focusing instead on their own questions. The same research shows that if you allow people to answer in their own way, it doesn't take any longer, and you get important information you might otherwise have missed. Questions about disease states and symptoms can miss the big picture. And we can miss the opportunity to reinforce both parties' shared responsibility for the patient's health.

Jacobs: I encourage patients to strive to learn and to communicate. Many patients may not thrive in a situation where they have many decisions to make and a care team to direct. That's natural! Learning your role — and asking lots of questions — is about the best way for the team to gel.

athenaInsight: Among the physicians we surveyed, 59 percent feel that patients should rely on their doctors for information about their diagnosis and condition. But patients have an increasing tendency to do research on their own, using many sources beyond their physicians. What's the best way for patients to manage information?

Jacobs: As part of our shared responsibility for healthcare, you should feel free to share the things you read online or watch on YouTube — it shows that you, as a patient, are engaged enough to inform yourself. But use your care team as a filter for the nearly infinite amount of online information. Bring your ideas, but also an appreciation for the formal expertise we earned with our medical training and an understanding that not all sources are reliable.

Myers: Along those same lines, it is important for patients to have realistic expectations for outcomes. I've personally had quite a bit of orthopedic surgery, because of accidents and sports injuries, and have come to realize that pain is just an everyday part of my life. I could mask it with narcotics, but that doesn't really make the pain go away. Or I could choose to move on, do what I can to stay healthy. I adjusted my expectations, and I strive toward function rather than total symptom relief. I think patients intuitively understand this when you take the time to explain.

Jacobs: And, perhaps most importantly, once a shared decision is made, patients should follow recommendations. Patients who don't are often not engaged or not fully embracing their role as decision makers. They feel they are “having things done to them." If we consider the team approach — with the patient as the decision-maker at the center — we can see the job of the patient requires attention and commitment. But being your own strongest advocate is a logical place to start and one where you'll be able to best harness the strength of your healthcare team.

athenaInsight: This lines up with what physicians told us — 73 percent say doctors must involve and even defer to patients as they devise strategies for lifestyle changes that will help the patient comply with medical recommendations. And 54 percent said physicians and patients must act as partners to stay on top of medication compliance.

Myers: At the end of the day, shared decision-making is the goal, based on candid and complete information and setting realistic expectations. People forget their actual lives can depend on these decisions, on whether or not they understand and are understood. The stakes couldn't be higher.

Lia Novotny is a contributing writer for athenaInsight.