It's well known that high-deductible health plans affect not only patients, but also the medical practices that care for them. As individuals take on more financial responsibility for their healthcare, patient obligations have gone up accordingly and now account for 18 percent of provider revenue.

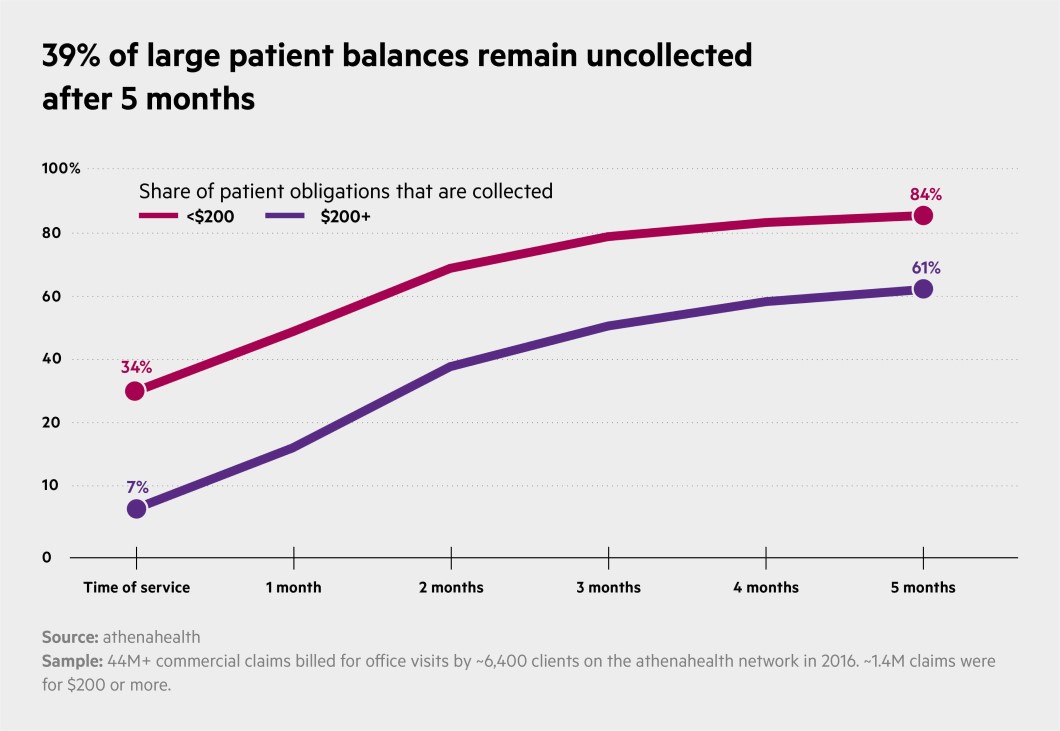

Also clear from practice data (and perhaps of no surprise): Collecting larger amounts from patients is typically a lot harder than collecting smaller obligations. One athenahealth network study, for example, found that practices collect about 40 percent of patient balances at the time of service when patients owe less than $35, but just 6 percent of what they're owed when the patient's balance is over $200.

Given that at most practices high-balance claims are relatively rare, does it make sense to invest limited resources in ensuring those claims are eventually paid?

The answer is yes, according to new data from athenahealth researchers.

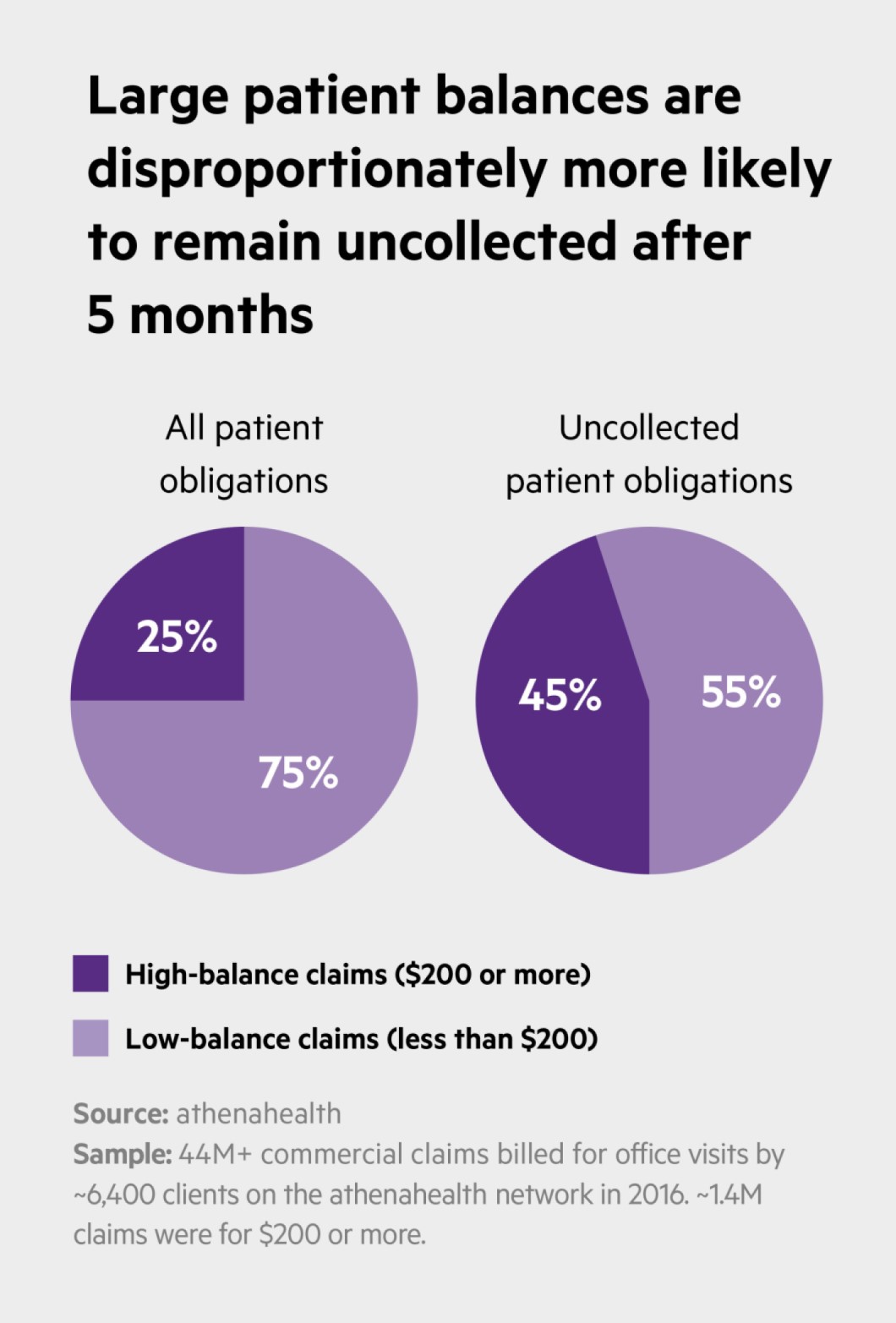

An analysis of more than 44 million commercial claims billed in 2016 by about 6,400 providers on the athenahealth network confirmed that only a small fraction of the claims were “high balance" – $200 or more. However, the data also show that high-balance claims comprise 25 percent of commercial patient obligations overall, and 45 percent of all obligations that remained uncollected after five months.

“The take-home message," explains Dorrie Raymond, director of research for athenahealth, “is that while fewer of your patients may have those high-balance claims, they're very important because they make up almost half of what goes uncollected."

Across specialties, Raymond says, providers collected about 61 percent of large patient obligations within the first five months of billing for a service. Still, she notes, some providers were “much better than others" when it came to collecting high-balance claims.

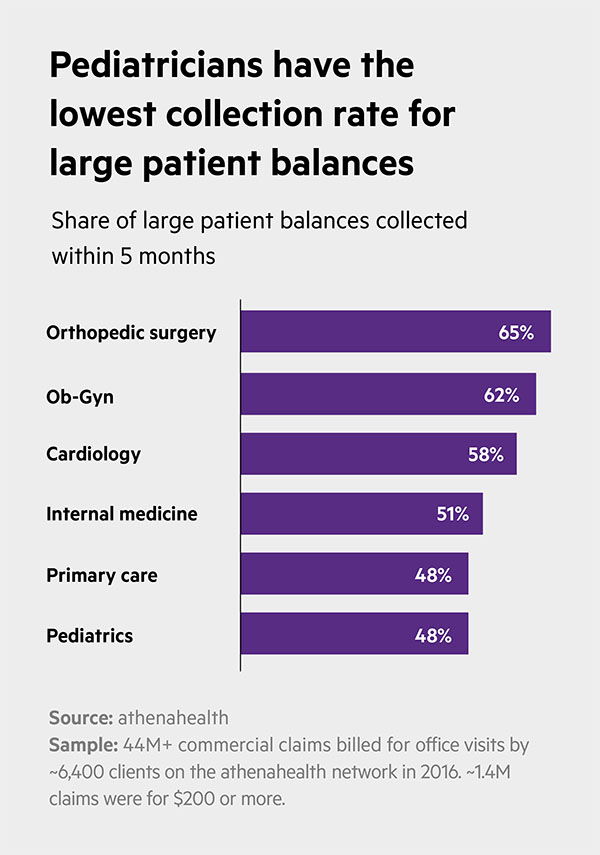

Orthopedic surgeons, for example, collected 65 percent of balances totaling $200 or more within that five-month post-service period, while primary care and pediatric practices each averaged just 48 percent collection rates. (Other specialty providers fell somewhere in between: Ob-Gyn practices at 62 percent; cardiology practices at 58 percent; and internal medicine practices at 51 percent.)

Why do certain specialties excel at high-balance collections while others seem to find such collections a struggle? “My guess," Raymond says, “is that patients in those specialties may expect higher bills, so they're more apt to pay them right away." Or, she says, it could be technique: “How you go about asking a patient to pay really can make a difference in the end."

Chris Hayhurst is a writer based in Northampton, Massachusetts.