Get a visual breakdown of the state of mental healthcare for mothers in the U.S.

Mothers, and new mothers in particular, have traditionally been overlooked when it comes to mental healthcare. Both childbirth and child-rearing put immense physical and mental stress on new mothers across the U.S., likely contributing to the high rates of perinatal and postpartum depression in the country. About 1 in 7 mothers experience perinatal depression within the first year of childbirth.1

Screenings have been proven for early detection and treatment when it comes to perinatal depression. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) are two common mental health screeners used by providers to detect perinatal depression across various demographics.

However, screening and treatment don’t always happen. About 60% of women with perinatal depression symptoms do not get a diagnosis, and about 50% of women who are diagnosed still don’t receive treatment.2 What’s more, some studies have found that as few as 5% of commercially insured women may receive a perinatal depression screening.3

To dig deeper into the state of maternal mental health, we set out to answer some questions on the probability of getting screened for perinatal depression across different races within our network of providers. We also hoped to learn if telehealth has the power to increase access to mental healthcare for mothers across the country. With what we’ve seen in the literature, we expected that average perinatal depression screening rates would be low. We also expected that some racial groups would not have the same access to mental health care via telehealth as others. Finally, we expected that telehealth might improve screening rates for some people.

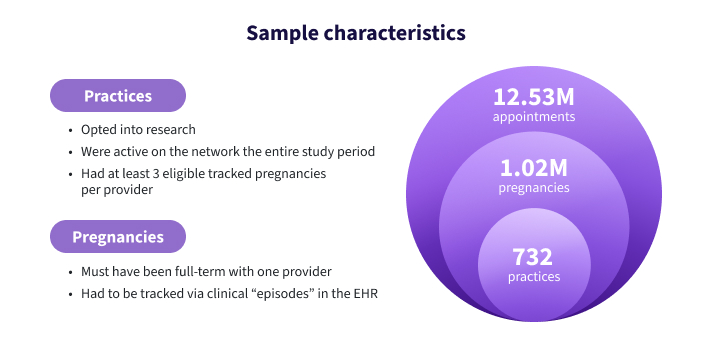

Leveraging the power of the athenahealth network, we examined data from over 700 different clinics and over 1 million pregnancies to answer these questions about maternal mental health.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into our methodology for this research.

Methodology – How we examined perinatal depression screening rates

To get a closer look at EPDS screening rates for new mothers across the country, our research team used a sample of 732 practices on the athenahealth network who were both opted into research, and active during the entire study period. The study period ran from 2020-2023 and included about 1.02 million pregnancies and 12.53 million appointments. To qualify for this research, practices needed to have at least three eligible tracked pregnancies per provider, and pregnancies must have been full term and tracked via “clinical episodes” in the athenahealth EHR. The raw data for this project was fully de-identified using HIPAA Safe Harbor methods prior to any analysis being performed.

Study design

- Measured screenings via completion of EPDS screener during perinatal visits

- Used a logistic regression to predict both the probability of receiving an EPDS screening and the impact of telehealth on the likelihood of screening

- Included an interaction effect to measure impact of telehealth on racial and ethnic screening differences

- The primary predictor variables of interest were race and telehealth use, but all models controlled for maternal age, number of visits, year of delivery, and insurance type during pregnancy.

With this methodology to conduct our research, we tried to anticipate the results based off what we’ve seen in similar research. Let’s dig deeper into our key findings below.

Key Findings – The state of maternal mental health and health equity for mothers in the U.S.

EPDS Screening Rates – Quick takeaways

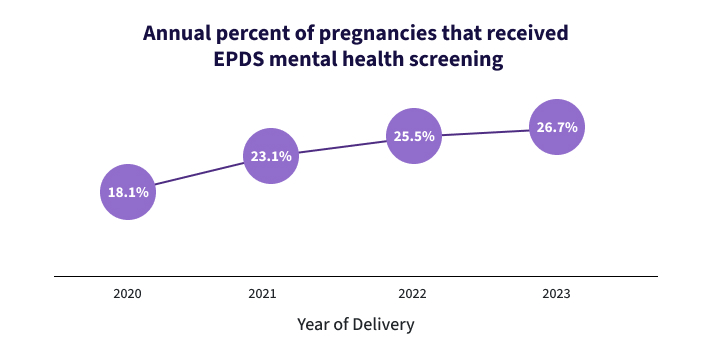

- While screening rates have been steadily increasing since 2020, the overall EPDS screening rates are still low, with an average of about 20-25% of pregnancies receiving EPDS screenings between 2020-2023. 17.5% of pregnancies that ended in 2020 received an EPDS screening, while 26.4% of pregnancies that ended in 2023 received a screening.

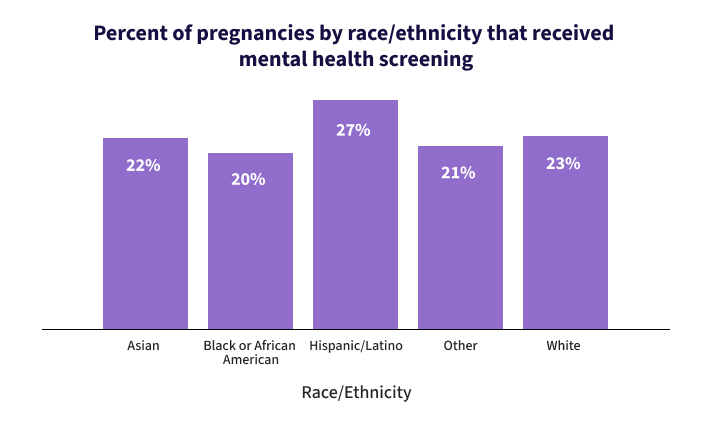

- Hispanic pregnancies had the highest percentage of screenings, with over a quarter (27%) of all pregnancies receiving a screening.

- White pregnancies were the second most likely to receive a screening.

- Black pregnancies had the lowest likelihood of receiving a screening at 20.5%.

“Overall, we found higher screening rates than other studies, some of which had rates as low as 4%. However, the majority of women in this sample were still not receiving screenings from their primary OB, and women from different racial groups experienced significantly different rates, suggesting that these screenings may be perpetuating maternal health inequality.”

- Allison Roberts, Quantitative Research Manager

Telehealth Impact on Screening – Quick takeaways

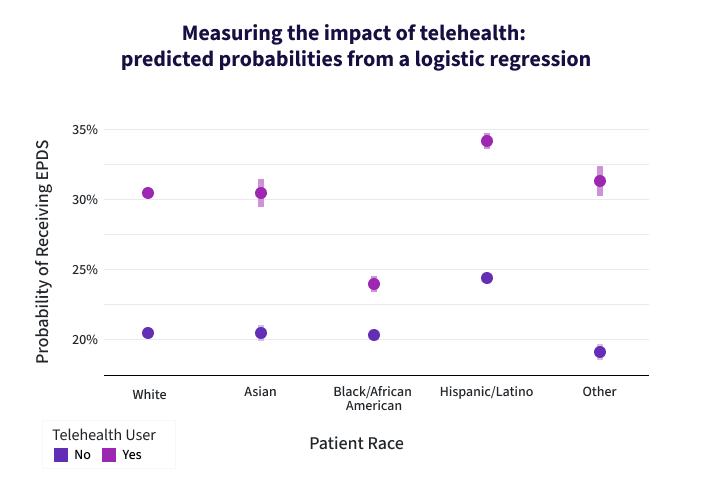

- The Research team built a predictive model (called a logistic regression) that predicts a woman’s likelihood of receiving an EPDS screening during or after pregnancy by racial status, telehealth use, and several demographic controls like age and insurance status.

- We found that telehealth use varies by racial group, even after controlling for demographic factors like age and insurance status.

- Hispanic and Latino women had over 25% of pregnancies receiving EPDS screenings, while all other races fell behind.

- Black and Hispanic patients were most likely to be covered by Medicaid, which matches national average enrollment estimates.

Racial Differences in Health Equity – Quick takeaways

- The most significant finding is that telehealth did not help all racial groups equally.

- Using the interaction effect between race and telehealth, we found that a White pregnancy where telehealth wasn’t used had a 21% chance of screening, but a White pregnancy where telehealth was used had a 31% chance (10% increase).

- Black women who didn’t use telehealth also had a 21% chance of receiving a perinatal screening. However, when using telehealth, Black women only saw a 3% increase (24% total). This suggests that access to telehealth helped White screening rates significantly more than Black screening rates.

As we’ve seen in other research, existing biases among physicians and lack of trust among patients can lead to lower screening rates. Black women may have less confidence that their concerns will be heard by their physician, and some providers may be less likely to provide them screenings. While we control for insurance coverage in this study, structural racism may result in Black women facing more socioeconomic hurdles: having less flexible work schedules, lower access to transportation, and lower incomes. This ties into the larger trend that Black mothers tend to have higher rates of other poor health outcomes, like higher maternal mortality and morbidity rates and higher infant mortality rates.

“These findings tell us both that telehealth can help women gain access to perinatal screenings, but also that it is failing to provide that access equitably. Access to telehealth in this case is clearly not enough—something is clearly happening after the point of access that is making it less beneficial for some groups.”

- Allison Roberts, Quantitative Research Manager

What providers can learn from this and future research on maternal mental health

Ultimately, we found that this research highlights important disparities in maternal mental health. These findings may inform actionable change for both physicians and EHR software providers like athenahealth. Women’s health clinics across the U.S. can benefit from knowing that not all mothers receive the same opportunities for mental health care and treatment, and that simply ensuring patients have access to tools like telehealth may not be enough.

Knowing that these disparities exist can help providers give additional support to vulnerable populations. Further, EHR companies can do more to ensure that providers have easy access to screening tools that flow seamlessly into the visit, allow for easy documentation, and allow patients to complete a screening prior to an appointment during digital check-ins. athenahealth is currently working with providers to identify pain points that we can address to improve screening rates.

In the future, the athenahealth Research team aims to analyze the link between screenings and depression diagnosis within this population. One critical area for follow-up research could be tracking perinatal screenings that occur in other settings, such as pediatric clinics, and determining whether those settings are as effective in ensuring the mother receives follow-up care. Another avenue could be to compare this research using the EPDS screening with other screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which is also commonly used in detecting perinatal depression. Overall, the Research team hopes to continue investigating which tools and factors drive the best possible maternal mental health outcomes, so this future work can help support mothers, athenahealth clients, and the larger healthcare community.

More athenahealth research resources

Explore more

1. NIH, “Postpartum Depression”, Aug 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/#:~:text=Postpartum%20depression%20(PPD)%20is%20a,the%20first%20year%20after%20childbirth.

2. NIH, “Postpartum Depression”, Aug 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/#:~:text=Postpartum%20depression%20(PPD)%20is%20a,the%20first%20year%20after%20childbirth.

3. NCQA, “Prenatal Depression Screening and Follow Up (PND-E)”, 2024, https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/prenatal-depression-screening-and-followup/